|

The Andreas CenterHome | About Us | Contact Us |

|

The Canon: Thoughts on the First-Generation Christian Literature 9. Into the Third and Fourth CenturiesHere are two episodes that take us from the early third century to the early fourth. The first is anecdotal and illustrates the kind of practical discernment people were obliged to make on the local level. The second is a contemporary survey of the state of the canon among the Eastern churches around 300 or a little after. a. Serapion of Antioch, the Church of Rhossus, and the Gospel of PeterSerapion was an elder of the church at Antioch in Syria at the beginning of the third century. (He died in 211.) In the course of his pastoral duties, Serapion learned of a disagreement that had arisen in the church in the nearby town of Rhossus. In their Sunday worship some apparently wished to read a book called the Gospel of Peter, and others did not. At first Serapion said, “If that is all that seemingly causes bad blood among you, let the book be read.” But later he found out that some in the church at Rhossus held to docetic teachings. So Serapion got a copy of the Gospel of Peter and read it himself. Docetists maintained that Christ’s human nature was not real but only an “appearance.” Their usual view was that the spiritual Christ came upon Jesus when he was baptized and left him before he was crucified. The Letter of 1 John is one of the earliest attempts to rebut such teaching. “The most part indeed,” Serapion said, “was in accordance with the

true teaching of the Savior, but . . . some things were added.”

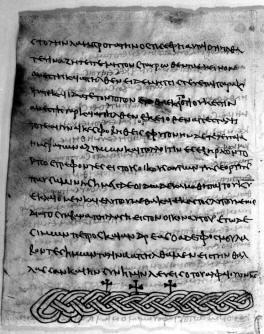

But the Gospel of Peter was not lost—or not completely—for a

long time. As late as the eighth or ninth century, six hundred years

after Serapion expressed his misgivings about it, the manuscript was

still being copied. A copy was placed in the grave of a Christian monk

who was buried in Egypt sometime between the eighth to

twelfth centuries. This copy was recovered in 1886–1887 when

archaeologists excavated the man’s grave, and it is now the only

surviving copy. (Translation in Hennecke-Schneemelcher 1:179-87). Decorations at the beginning and end of the manuscript show that the copyist of the Gospel of Peter reproduced all he had of it, but what he had was incomplete: a portion of a passion narrative, beginning with the legal proceedings of Pilate and Herod and including the crucifixion, the burial, the resurrection, and the beginning of an appearance in Galilee, where the fragment breaks off. What is left of the Gospel of Peter does bear out Serapion’s

opinion of it. The book contains elements of the canonical Gospels along with details or inferences that are sometimes

innocuous but that sometimes betray systematic motivation. Here are

examples of the tendentious elements: • Herod, not Pilate, commands the execution, and Pilate is exonerated. • When fastened to the cross, Jesus “held his peace, as if he felt no pain.” • Jesus’ legs were not broken, so he might

suffer longer. • The words, “My God, My God, why have you

forsaken me?” become, “My Power, O Power, you have forsaken me!” •

The resurrection is witnessed by the

soldiers and Jewish elders watching with them. • The emergence of Jesus from the tomb is visionary: he walks out between two figures, and he is taller than either of them (“overpassing the heavens”), and he is followed by a cross that speaks. (Well, it says one word: “Yes.”).

But is the Gospel of Peter docetic? Not much, judging from what there is of it. But it is moving away from the New Testament atmosphere—even if only a little—and toward something foreign. This is what moved Serapion ultimately to conclude the book should not be read. The story illustrates the kind of practical decisions church leaders made about the legitimacy of various writings and their use in worship: local churches had a good deal of autonomy in the matter. It also illustrates the popularity of secondary literature—then as now.

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

|

Gospel of Peter. The manuscript in the Cairo Museum. This is the last column of text, which breaks off in mid sentence and is followed by the decoration.

|

|

Home | About Us | Contact Us |

|